Mires explotation and destruction in the Chilean Patagonia as a consequence of insufficient environmental regulations

(Short communication published in the Bulletin 1016 of the International Mire Conservation Group IMCG: http://www.imcg.net/media/2016/imcg_bulletin_1610.pdf)

In Chile 3% of the national territory is covered by mires and peatlands, meaning approximately 4.600.000 ha (CONAF, 1999). Of these ecosystems, almost 70% are located in the Chilean Patagonia, covering from the region of Los Lagos until Cape Horn in the region of Magallanes. Patagonia is one of the last regions in the world where natural mires still grow intact and in pristine conditions. Some international agreements signed by Chile are indirectly related to mires: the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and the Kyoto Protocol of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Nevertheless, considerations of ecological consequences are little of an issue in front of productive activities in that country. Subsequently, so called “environmental catastrophes” are frequent; in 2016 for instance the massive occurrence of the red tide in Chiloé caused by eutrophication derived from salmon farms (see e.g. National Geographic, 2016) or the contamination of the drinking water in the capital Santiago (see e.g. FSNR, 2016). The progressive destruction of mire ecosystems is only one point more, on the list of the non-awareness and neglect of the ecological consequences by politicians and institutions.

So far, due to their geographical isolation mire ecosystems in the Chilean Patagonia remain rather protected from industrial contamination and from exploitation initiatives. But this situation is changing with support and commitment of the Chilean government. Special attention lies in the Region of Magallanes, where after recent calculations app. 269.545 hectars of Sphagnum mires are located (Domínguez & Vega-Valdéz, 2015). In this region, on the one hand, the National Institute for Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIA) investigates and researches actively the harvest and commercialization of Sphagnum magellanicum moss. Through workshops, bulletins and talks, this institution induces local communities and entrepreneurships to invest in the harvest, drying and product development based on this peat forming species. The growth rate of living Sphagnum magellanicum mosses calculated by the INIA from renaturation experiments is 2 to 5 mm year-1 under outdoor conditions (Domínguez & Larraín, 2013). Under this rate, a sustainable management of these mosses could only be realized if the harvested areas are allowed to rest for 30 to 75 years, which is the time needed by new Sphagnum strings to reach 15 cm length. But living plants are not the only threatened part of mire ecosystems. Peat, on the other hand, is defined in Chile by the Mining Code (Ministerio de Minería, 1983) as a “non-metallic resource”. Since mining activity is the most important basis of the Chilean economy, potential exploitable mining resources are given special preference and are considered to be above environmental regulations. This policy was accentuated during the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1989) who defined mining concessions as “a right in rem and immovable, separate and independent of the domain of the surface property, even if they have the same owner, enforceable against the State and any person, transferable and transmissible; susceptible to mortgage and other property rights and, in general, of all act or contract…” (Minería, 1983). Currently, the Mining Ministry through its Regional Office (SEREMI or Secretaría Regional Ministerial) is actively promoting the research and investment in peat mining in Magallanes. This Ministry signed an agreement with the World Conservation Society (WCS) in July of 2015, which administrates the Natural Park Karukinka in the Island of Tierra del Fuego (Minería, 2015). Circa 10% mires of Magallanes are located in Karukinka Park, meaning 25.000 has approx. The agreement specifies that mires inside Karukinka can only be intervened for research issues and peat mining can be allowed under special conditions. Suddenly, all other mires covering in the whole Chilean Patagonia are excluded of the agreement and can be mined (Minería, 2016).

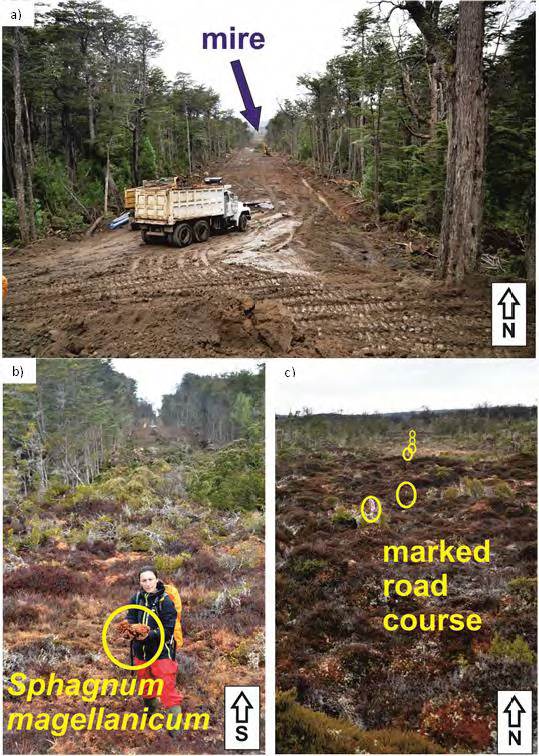

In the region of Magallanes mires are important ecosystems retaining fresh water in the landscape, a very important resource since the area is seriously affected by its scarcity. Some sections of these ecosystems are also covered by forests, e.g. of Pilgerodendron uviferum (a cypress species protected by law in Chile), allowing a mosaic of habitat niches for endangered fauna like the e.g. Strix rufipes (Díaz-Tavié, 2016). In the province of Última Esperanza, one of the Magellan province with the highest presence of mires (Ruiz & Doberti, 2005), constructions works on behalf of the Ministry of Public Works (MOP-Ministerio de Obras Públicas) begun earlier this year, for a road connecting the settlements Seno Obstrucción and Río Pérez (Figure 1), allowing an alternative connection with the regional capital Punta Arenas. The planned course of the road will cut one of the biggest mire complexes of the province in two affecting its hydrological and ecologic balance (Figure 2). Further, even though the new road is primarily built to facilitate the expansion of the salmon industry and coal mining, it is likely to induce peat exploitation as well, as isolation was always the best protection mires had. Consequently, the road will facilitate the access to moss harvest and peat mining areas that otherwise could not be reached. Until the send of this communication, the Mining Ministry, which is obligated to give information about peat mining concessions, did not responded to our requests.

Destructive effects on mire ecosystems have been already registered after the completion of the Carretera Austral in the region of Aysén in Chile. Its construction affected over 6000 hectars of mires through the structural division of these ecosystems (Figure 3), and the removal of peat layers for extraction of aggregates, and the drainage/flooding of the affected areas with ecologic and hydrologic unbalances for the whole mire complexes (Rodríguez, 2015).

These antecedents show that Chile is not applying serious regulations related to mire protection and that the importance of these ecosystems is still overseen by local authorities. In order to raise awareness about mire ecosystem functions, between May and July 2016 the mire experts Marvin Gabriel and Ana Carolina Rodríguez undertook an initiative to educate children and teachers of the town Puerto Natales, about the importance of regional mires. In coordination with the local Environmental Department of the Municipal Corporation for Education, several scientific workshops were developed about mire ecological functions and protection with scholars in the local schools (Figure 4). The children and teachers were introduced to mire plants, peat and some of their functions like water retention, water purification and ecological linkages of these ecosystems, which are very present in their province. It is expected that local environmental institutions reply such initiatives and educate people from a scientific perspective, rather than from a short term productive one. Otherwise mires in Chile will be put in risk and with it the chances of future generations to benefit from their ecosystem functions.

These antecedents show that Chile is not applying serious regulations related to mire protection and that the importance of these ecosystems is still overseen by local authorities. In order to raise awareness about mire ecosystem functions, between May and July 2016 the mire experts Marvin Gabriel and Ana Carolina Rodríguez undertook an initiative to educate children and teachers of the town Puerto Natales, about the importance of regional mires. In coordination with the local Environmental Department of the Municipal Corporation for Education, several scientific workshops were developed about mire ecological functions and protection with scholars in the local schools (Figure 4). The children and teachers were introduced to mire plants, peat and some of their functions like water retention, water purification and ecological linkages of these ecosystems, which are very present in their province. It is expected that local environmental institutions reply such initiatives and educate people from a scientific perspective, rather than from a short term productive one. Otherwise mires in Chile will be put in risk and with it the chances of future generations to benefit from their ecosystem functions.

Sources

CONAF, C. N. F., 1999. Catastro de Recursos Nativos, s.l.: s.n.

Díaz-Tavié, J., 2016. Personal communication. Puerto Natales: s.n.

Domínguez, E. & Larraín, J., 2013. Sphagnum magellanicum (pompón): El musgo de la turbera., s.l.: Tierra Adentro.

Domínguez, E. & Vega-Valdéz, D., 2015. Funciones Ecosistémicas de las Turberas en Magallanes. Punta Arenas: s.n.

FSRN, 2016. Free Speech Radio News. [Online]

Available at: https://fsrn.org/2016/04/massive-water-shutoff-in-chilean-capital-highlights-long-struggle-over-resource-management/

[Accessed 03 09 2016].

Minería, M. d., 1983. Código de Minería. Santiago de Chile: Junta de Gobierno Militar de la República de Chile.

Minería, M. d., 2015. “Declara lugar de interés científico para efectos mineros área ubicada en Región de Magallanes, Provincia de Tierra del Fueo, Comuna de Timaukel”. s.l.:s.n.

Minería, M. d., 2016. Cuenta Pública. Santiago de Chile: s.n.

National Geographic, 2016. National Geographic News. [Online]

Available at: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/05/160517-chile-red-tide-fishermen-protest-chiloe/

[Accessed 04 09 2016].

Rodríguez, A. C., 2015. Hydrogeomorphic classification of mire ecosystems within the Baker and Pascua Basins in the Region Aysén, Chilean Patagonia: a tool for their assessment and monitoring. Berlin-Germany: Humboldt Universität zu Berlin.

Ruiz, J. & Doberti, M., 2005. Catastro y caracterización de loe turbales de Magallanes, Punta Arenas: s.n.