El norte de Chile no es sólo un desierto. Allí hay importantes ecosistemas que almacenan agua, proveen biodiversidad y protegen el clima. Al respecto, te invitamos a leer nuestro nuevo post sobre los Bofedales, las turberas del altiplano.

Pequeño artículo sobre las turberas del sur de Chile

Les dejamos el Nro. 10 de la Revista PRISMA del Centro de Humedales del Río Cruces, sobre las turberas del Sur de Chile:

Puedes descargarla desde: http://www.cehum.org/prisma/

Retraso del Decreto N°25 (2017) que propone regular la cosecha de Sphagnum magellanicum en Chile

El gobierno de Chile, presidido por Sebastián Piñera, atrasó la entrada en vigor del Decreto N°25 (2017), una herramienta legal que tendría la función de finalmente regular la cosecha del musgo Sphagnum magellanicum en este país. Esta regulación debía entrar en vigencia en Agosto de 2018. La nueva fecha para su entrada en vigencia es Agosto de 2019. La razón por la cual el decreto fue postergado es la tremenda presión por parte de las empresas cosechadoras y exportadoras de Sphagnum en Chile. Tristemente, esto ha traído como consecuencia una gran “Fiebre del musgo”, el cual aún puede ser cosechado sin regulación por el plazo de un año, o hasta la entrada en vigencia de dicho Decreto. Personas de comunidades cercanas a turberas han reportado la proliferación de nuevos focos de cosecha en Aysén y Magallanes, incluso en turberas ubicadas en terrenos pertenecientes al Estado (Ministerio de Bienes Nacionales). Chile da así un paso atrás en el camino de la conservación y protección de estos ecosistemas.

Legislación para la protección del Musgo Sphagnum en Chile

Estamos muy felices que de el gobierno por fin haya generado una Norma para proteger el musgo Sphagnum magellanicum, principal componente florístico de las turberas elevadas de Patagonia. La nueva “Norma General CVE 1346055” decreta un largo máximo de corte de las hebras del musgo, periodos mínimos de descanso de las áreas cosechadas (12 años para la región de Los Lagos y Chiloé, y 85 años para las regiones de Aysén y Magallanes), prohibición del drenage en las áreas de cosecha y una serie de otras medidas que ayudarán a que la extracción se regule y los ecosistemas de turberas puedan prevalecer en el tiempo.

Aquí puede leerse el decreto publicado en el Diario Oficial: http://www.diariooficial.interior.gob.cl/publicaciones/2018/02/02/41973/01/1346055.pdf

Felicidades al pueblo de Chile, por haber tomado tan importante decisión de conservación!. Felicidades a todas las personas que influyeron en que esta medida fuera posible, especialmente a las personas de Parque Etnobotánico Omora, Aysén Reserva de Vida, Round Rivers Conservation, Vive Aysén, Centro de Investigación en Recursos Naturales y Sustentabilidad-CIRENYS, Senda Darwin, Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero-SAG de Coyhaique, al Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agropecuaria INIA de Magallanes, al Departamento de Suelos de la Humboldt Universität zu Berlin y a cada persona que con su conciencia y entusiasmo aportó a construir esta nueva realidad para las turberas de Chile. Ahora, a seguir protegiendo las turberas y difundiendo su importancia.

Compartiendo saberes para la protección de las turberas en la región de Aysén

Gracias a nuestrxs amigxs de Aysén Ahora Noticias por esta pequeña nota, sobre la charla que hicimos para la comunidad en la Casa de la Cultura de Puerto Aysén. Y especialmente va nuestra gratitud para al equipo de Vive Aysén, por apoyar la difusión de estas informaciones a nivel comunitario, invitando y haciendo posible ese espacio.

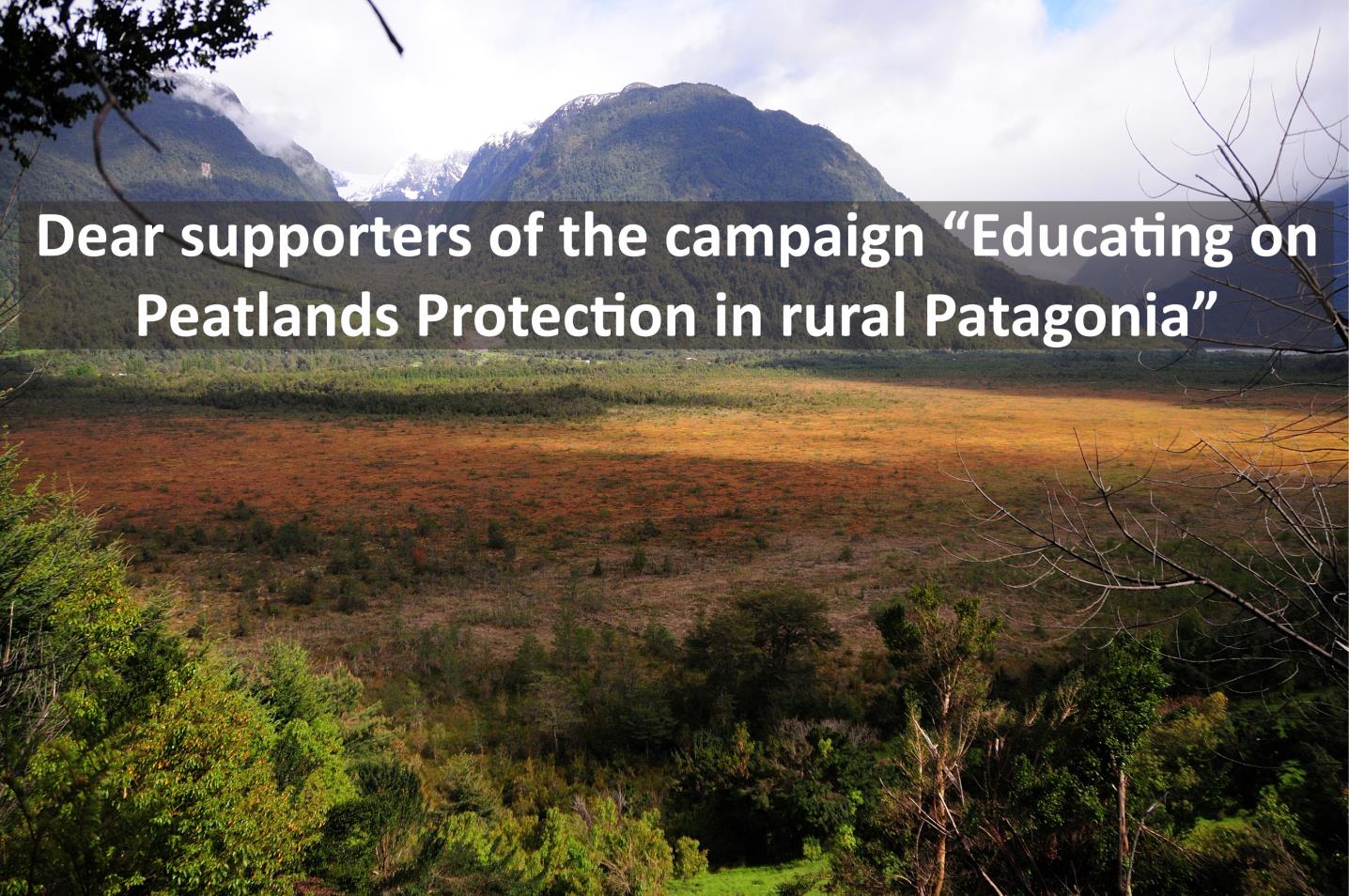

Una campaña exitosa

(Pronto en español)

Thanks to all your support we were able to realise the journey to rural communities of the Chilean Patagonia in between the 10th of November and the 9th of December 2017. The timeframe of the trip was determined by the necessity of good weather conditions and the school vacations. The pupils in Chile leave the school by mid December and have a long summer vacation until March, so the best time window was late springtime.

The trip was also well timed for another reason. At the moment, the harvesting of the peat moss (Sphagnum magellanicum) is expanding into the Chilean Patagonia. Since many years, this activity was exclusively practised in the Chilean region Los Lagos. Properly managed, with sufficient time for regeneration and a harvest not below a certain depth, peat moss can be considered a regrowing resource. However, the unsustainable way of harvesting peat moss let to a depletion in the region Los Lagos, wherefore this economy is moving southwards and continues in the same way. The growth of road systems and infrastructure unfortunately also makes the formely isolated peatlands accessible, which are amongst the last pristine peatland complexes in the world. As you can see in the photos, we also came across the transport chain.

As many people in the Patagonia are worried about the expansion of the peat moss harvest into their region, we were invited in some communities to give presentation with background information on peatlands, discussing their functions (e.g. water storage, carbon storage, protection against inundations, special habitat for plants and animals) and the risks related to the peat moss harvest.

The Team

First of all, we present the team: Mariana, who worked several years in the wetlands of the Maipo River as a ranger and as an environmental instructor for kids. Caro, who wrote her PhD thesis about the classification of peatland types in the region of Aysén and has a long-standing experience working on environmental education. And Marvin, who is just about to finish a PhD about peatlands in South Africa and instructed various environmental education projects before.

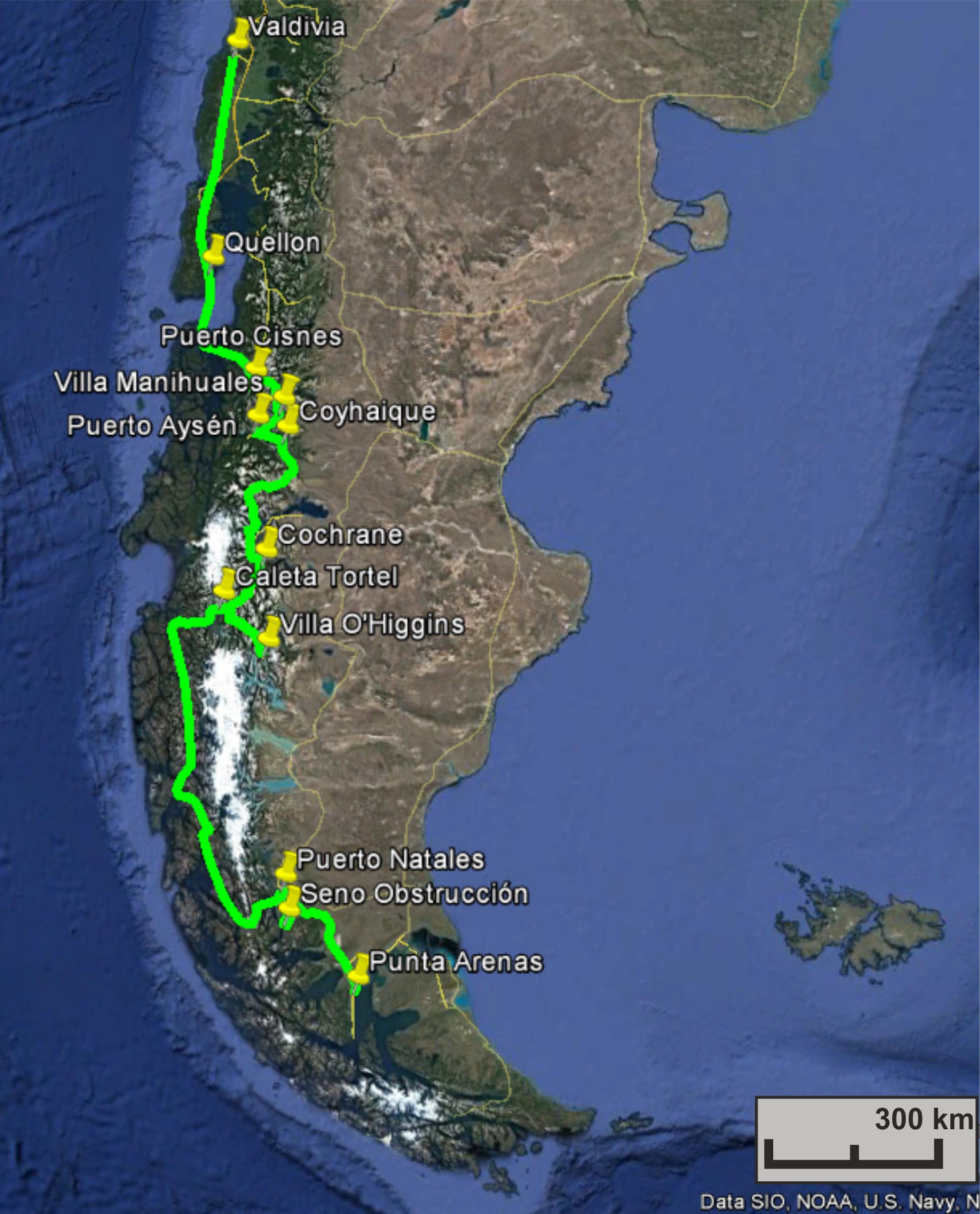

The Journey

The route that we took brought us in the first half to the southern end of Chiles famous Carreterra Austral. The second half was done in the region Magallanes. Moving by public transport (buses and ferries) with a suitcase full of indoor-workshop equipment, a heavy bag with a peat corer for the outdoor part of the workshop and all the stuff we need for camping. At first we went to a small rural community named Villa Manihuales, where we conducted a workshop with 28 kids of the local school. Later that day, we went to Puerto Aysén where we gave a presentation about Peatlands in Aysén to the community.

From there on we moved forward to Coyhaique, where we were invited to two radio sessions to talk about the peatland problematic and also gave a community talk. After a one evening stop and another community talk in Cochrane we went forward to Villa O’Higgins, the last village of the Carreterra Austral where we met a student group of the US-American NGO Round River Conservation Studies. They work in Patagonia in environmental monitoring programmes and together we organised the workshop with the schools in Villa O’Higgins and Caleta Tortel. Both times we took the kids to peatlands in walking distance and every child of the school had its personal buddy from the US-student group.

In addition, we gave in each place a radio and a community talk. Moreover, in Caleta Tortel, we were asked by a member of the municipal council to give a presentation, so we prepared a short and concise talk, about risks (extractive peatland use) and possibilities (non-extractive peatland use) for the local politicians.

A two day journey on the vessel Crux Australis brought us through the channels of the Patagonian Archipelago to Puerto Natales and the region Magallanes. It took us a couple of days to get the programme organised, permissions from the parents and to see how the transport will work. On the way, Matias Muñoz, a teenager student of the school Puerto Natales joined us as enthusiastic voluntary field assistant. In the end we took children from the school E3 Santiago Bueras of Puerto Natales to the rural school of Seno Obstrucción, where they joined the pupils of the rural school of Seno Obstrucción. The small village, some 60 km south of Puerto Natales, is surrounded by peatlands and some of the approximately 50 inhabitants live from harvest of peat mosses. For the three pupils of Seno Obstrucción, who rarely meet other kids, it was a delightful encounter, and for the pupils of the school Santiago Bueras of Puerto Natales a great adventure.

The indoor activities usually consisted of experiments aiming to illustrate the differences between peat and mineral soils, the water storage and filtration capacities of peat, as well as to teach the recognition of peatland plants by fotos and samples. The second part outside, aimed to sharpen the pupils perception of the environment, to recognise peatlands as elements of the landscape, encounter typical plants and animals and discover the part which is below the surface (using the peat corer generously donated by the FG Bodenkunde of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin).

Altogether we left the south of Chile with a good feeling about our activities. We got the impression of having left some seeds of environmental awareness, which might flower in the future. Further, we are happy that thanks to the donations, we were able to act as an independent initiative, without representing the interests of the private economic sector; or governmental institutions, which are usually biased in favour of economic (extractive) activities.

Many thanks also go to the angels who helped us along the way:

Gabriela Núñez+Nico+Amparo+Amanda y Erick Vidal (Puerto Aysén)

Peter Hartmann y Dinelly Soto (Coyhaique)

Matthew Pomilia, Eli Brunner, Shalynn Pack and the Round River Conservation students (Villa O’Higgins and Caleta Tortel)

José Diaz Tavié; Ricardo Ordóñez; Sabine Barrios+Livio +Simón; Roberto Muñoz+ Matías+ Claudia (Puerto Natales y Seno Obstrucción)

List of activities in chronologic order:

– Workshop with school in Villa Manihuales

– Community talk in Puerto Aysén

– Community talk in Coyhaique

– Community talk in Cochrane

– Workshop with school in Villa O’Higgins

– Community talk in Villa O’Higgins

– Workshop with school in Caleta Tortel

– Presentation to the community council in Caleta Tortel

– Community talk in Caleta Tortel

– Joint workshop in Seno Obstrucción, with the rural school of Seno Obstrucción and the school E3 Santiago Bueras of Puerto Natales.

Map of the journey with all its stations

Taller “Turberas: Puesta al Día y Desafíos”

El pasado miércoles 14 de junio de 2017 participamos del taller “Turberas: puesta al día y desafíos” en Santiago, presentando nuestra iniciativa “Mires of Chile”.

Allí tuvimos un fructífero intercambio con colegas que trabajan en conservación, restauración e investigación sobre turberas, tales como Verónica Pancotto (CADIC – CONICET-Argentina), Carolina León (Universidad Bernardo O’Higgins), Christel Oberpaur (Universidad Santo Tomás), Ariel Valdés (Universidad de Chile), Rubén Carrillo (Universidad de la Frontera), Erwin Domínguez (INIA Kampenaike Magallanes), Leonardo Fernández (Universidad Bernardo O’Higgins) y Roy MacKenzie (Parque OMORA-Universidad de Magallanes). Esperamos que este proceso de lugar a nuevas sinergias y trabajos cooperativos por la protección de estos ecosistemas y sus funciones clave para la prevención del cambio climático.

INVITACIÓN A CHARLA “Las Turberas de la Patagonia Austral: Propuestas para su Reconocimiento, Valoración y Conservación frente a la Amenaza de las Industrias Extractivas”

Todxs están cordialmente invitadxs a esta charla a ser realizada en Valdivia este jueves 18 de mayo de 2017 a las 11:30 hrs (Sala Patricio Barriga/ Escuela de Graduados/ Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias / Universidad Austral de Chile-Campus Isla Teja)!

La Degradación de Turberas

Una nueva contribución para el reconocimiento de procesos de degradación en turberas prístinas e intervenidas está disponible en nuestra sección sobre Conservación y Restauración.

Sustratos en turberas de Aysén y la Patagonia Chilena: documento descargable

http://www.miresofchile.cl/PDFs/Fichas_Reconocimiento_Tipos_Sustratos.pdf